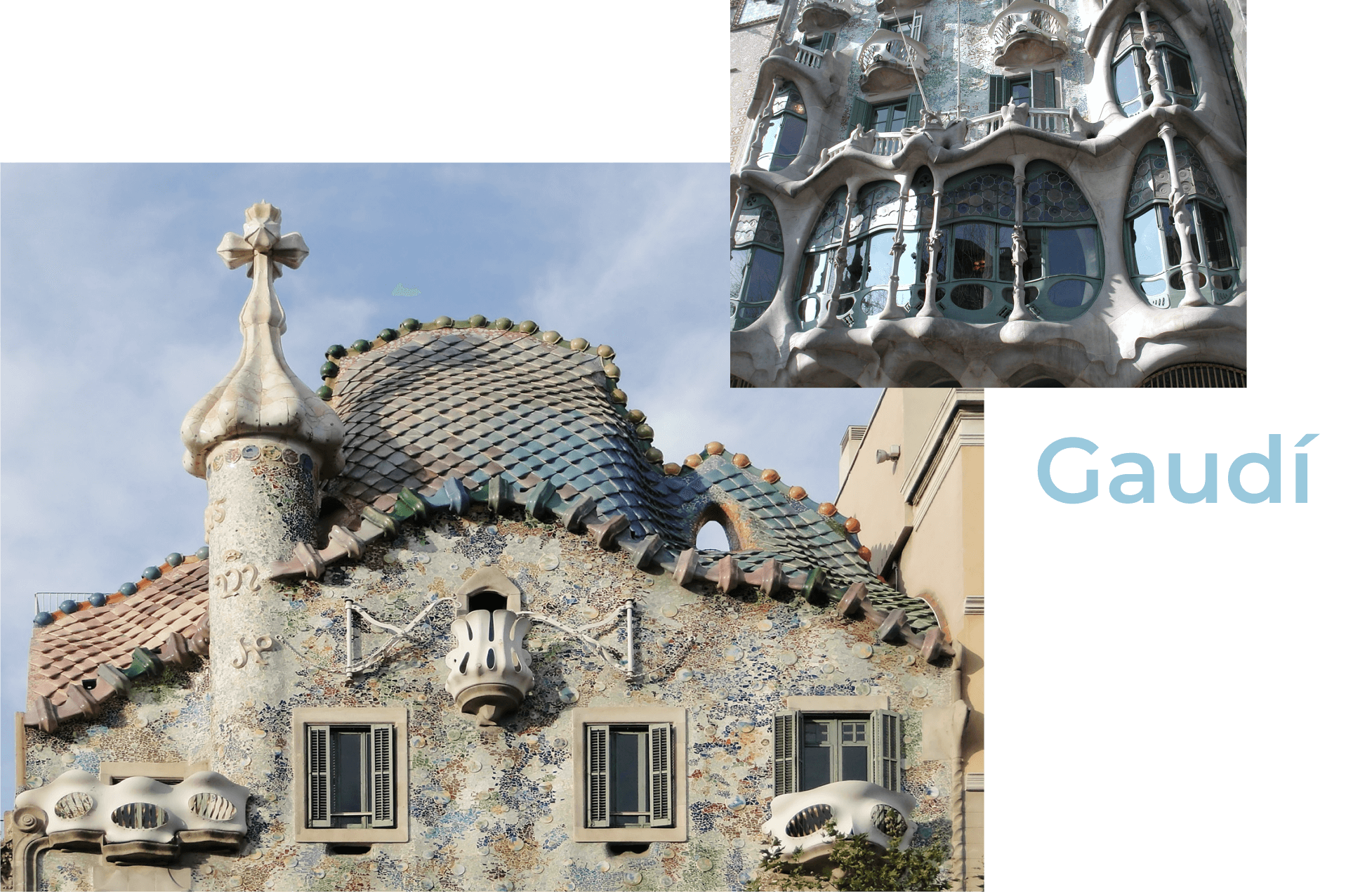

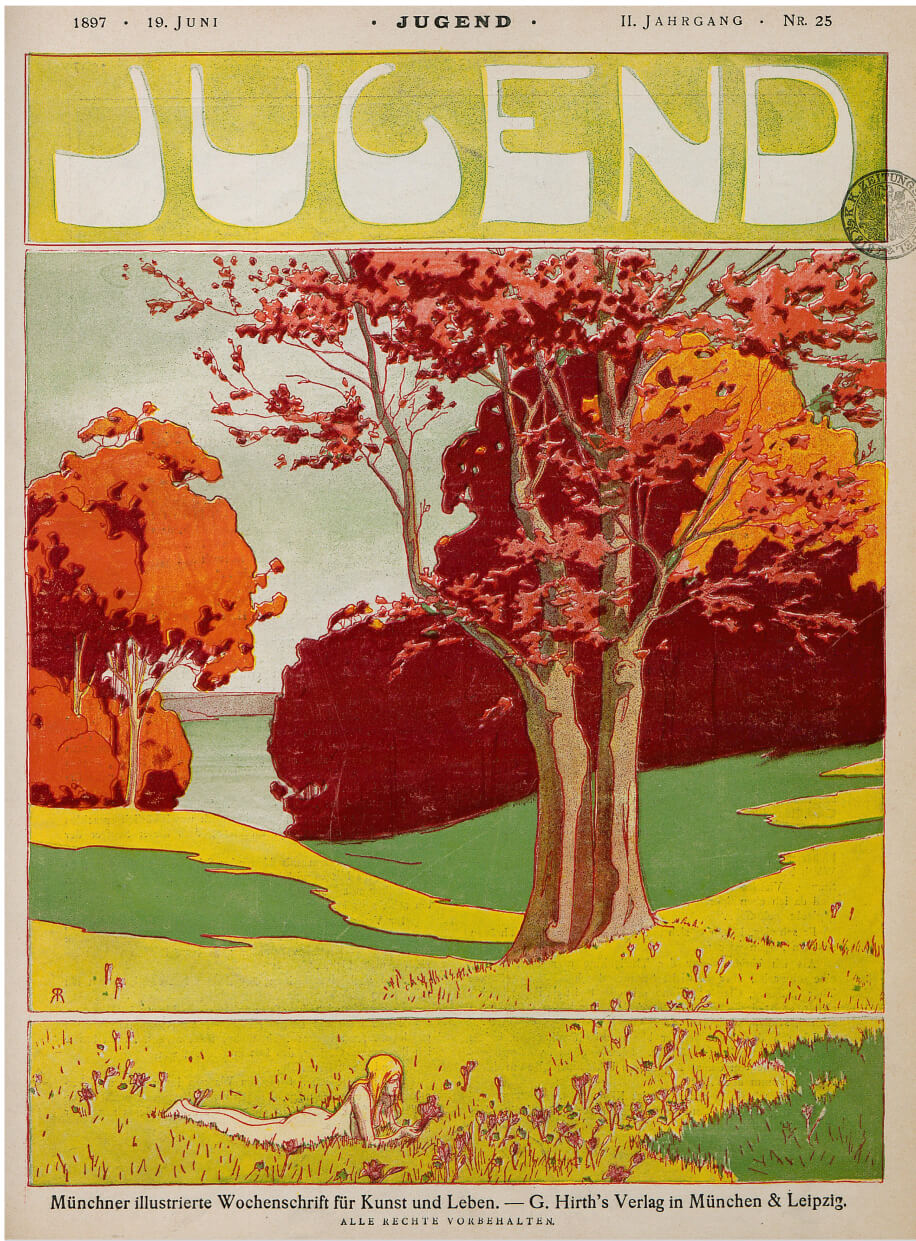

What is Art Nouveau?

Art Nouveau was a short but intense phase in art history around 1900 – in Europe between about 1890 and 1910 and in Germany almost exactly between 1897 and 1907. Art Nouveau marked the beginning of Modernism in architecture and design.